|

Hanley Deep Lane & a

lost Chartist

On 13th August 1842 leading Chartist Thomas Cooper addressed a large crowd of striking coalminers in fields where Hanley Forest Park is today. Some historians claim that Cooper’s inflammatory speech to illiterate potters provided the spark that fired the local Chartist Riots and civil confrontation and death in Burslem two days later. Realising the tone of his speech had instigated widespread drunkenness and vandalism Cooper decided to flee to Manchester the night before the Burslem Riots. His escape route led from Hanley to Biddulph along High Lane but in the darkness he missed his way and found himself in the centre of Burslem where he was arrested. The unlucky lane that Cooper took is surprisingly still traversable.

“You’ll recall we did the Burslem section of the lane back in December,” my companion Peter Adams reminds me of a previous walk along Cow Lane. “At that time we followed the Burslem side that led us through Sneyd Colliery, so I thought it’d be interesting to have a look at the Hanley end.”

Peter was born on Burslem Park Estate 69 years ago and knows the twists of the lane much better than Thomas Cooper did.

“Remember, it leaves Burslem through Sneyd Colliery and crosses Sandbach Road top side of Sneyd Cricket ground where it travels over Leek New Road into Spa Street and into open fields,” Peter prompts me.

Gazing from the top of these fields, once known as Roehurst, a rarely seen vista of Burslem is revealed over land that reels like a turbulent sea of disused mines and abandoned works. The great mound of Sneyd tip is the dominating feature towering above the little town where the town hall crouches like a dolls house. It is all strangely distant and unfamiliar.

“As a lad I’d wander far away from home,” Peter continues. “But I could still see my house from here. In those days the spirit of adventure inspired every child. I’d become lost in a wonderland world. Off early in the morning, my mother wouldn’t have a clue when I’d be back.”

Roehurst fields have changed little. Uneven clumps of wild grass hide vanished smallholdings hidden forever beneath copses of willow and silver birch and giant thickets of blackberry bushes. An odd unused shed lies abandoned: who owns this wilderness I wonder.

“Everything then was useful,” claims Peter. “Nothing was thrown away. In the war American trucks queued at Sneyd colliery loading red ash from the tip to make aircraft runways across the country. Red ash was used to mix with concrete. It was used to make building bricks and along with broken saggars people would build walls with it. Nothing was knocked down – it was simpler to add-on than rebuild.”

the remains of the

pithead gear on Town Road at Hanley Deep Pit

[now removed]

photo: Anne Buckland

The reclaimed and grassed

spoil heaps of Hanley Deep Pit

photo: Anne Buckland

Above Roehurst is Sneyd Street, another ancient lane used by Abbey Hulton monks travelling to Cobridge. Crossing here Peter leads me through the streets of a new housing development where our track has been diverted only to suddenly reappear at the foot of the two mighty waste tips of Hanley Deep Pit.

“This marks the west side of the Shelton Colliery owned by Granville’s,” Peter informs me. “It was the deepest pit in the area before Wolstanton was enlarged. But notice that our path runs between these twin industrial towers quite neatly. This is because the path travelled this way long before industrialised coalmining produced these huge mounds. There was so much waste that the owners had to pile it into two heaps so as not to block the public right of way.”

Standing like dark sentinels these dismal hills were tamed in the 1960’s and dressed in cloaks of greenery. Now they provide a dramatic backdrop to the leisure bowl that has become the Central Forest Park, an outstanding gateway to the City Centre, a sanctuary for wildlife and human creatures to share equally.

“Don’t worry, you can still follow the old path,” says Peter directing me through the maze of a children’s playground and a skateboard and Rollerblade Park. “Some of the path has been covered with tarmac but you can just see where it travels across the fields to an opening on the main road as it enters Hanley.”

And this is where lane ends, where Thomas Cooper lost his way 165 years ago. It actually brings you out alongside Walker’s Greengrocers, itself a landmark among the confusion of streets at Providence Square. Even today it’s easy to become mixed-up in the frustrating mishmash of converging roads where the boundaries of Sneyd Green, Birches Head, Northwood and Hanley meet. The grandson of the founder of Walker’s Greengrocers is 78 year old Arthur Walker.

“My grandfather had a coal business and my grandmother was a Hawley who owned the greengrocery which was then further along on the corner of Ricardo Street,” recalls Arthur. “In 1939 we bought the shop where we are now for £750. The path at the side led into red ash fields known as the Hollies and it passed between the two tips one of which was burning for years.

My dad Harry walked this lane every day to Cobridge where he was head thrower of Moorcroft’s exhibition pottery. There were many terraced streets here when I was a boy, most have been demolished. Of course the big feature was Hanley Deep Pit that ran from the Square to Union Street almost reaching Hanley town centre.”

[Note: Ricardo Street,

Hanley was renamed Merrick Street in the 1950's]

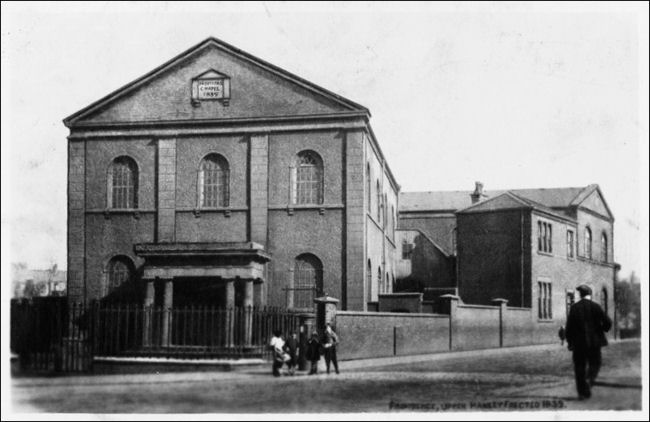

postcard of Providence Chapel,

Upper Hanley, Erected 1839

provided by: John Booth

Arthur’s recall of long vanished businesses is impressive.

“The Providence Chapel once stood in the middle island,” he recounts.

“Next door was Gommersall’s pawnbroker. Then Baddeley’s who made tin water-bottles for the miners, Ted Buckley’s barbers, Tom Jones tobacconist, Kirkham’s butchers and Foxall’s greengrocers; Finney’s and Weatherby’s, Baxter’s Buses depot, Ibbs removals, a Chinese laundry, a clog shop and Watson’s piano shop. Providence Square always has been a tricky but important road junction.”

Just think all this going on beneath the Forest Park and the busy road junction. It’s no wonder poor Thomas Cooper managed to get himself lost.

Fred Hughes

|

![]()

![]()