|

the history of Longton Cemetery

click the

"contents" button to get back to the main index & map

next: Hanley Cemetery

previous:

Burslem Cemetery

|

Historian Fred Hughes

writes....

Diane McDaid’s neighbours won’t be calling round for a festive drink this

Christmas; she says they’ve already got enough spirits. The owner of a

popular Stoke on Trent restaurant Diane has plenty of friends who are very

welcome to call for a drop of cheer; it’s just the neighbour’s who won’t

be getting an invite. And the reason for this parsimonious inhospitality

is simply that Diane’s neighbours are all dead.

“Earlier this year I bought Longton Cemetery Lodge from the council,”

she tells me. “I fell in love with the mock-Tudor detached building as

soon as I saw it. I suppose living in a cemetery would put most people

off but my passion is restoring and changing the use of public

buildings. For instance my conversion of the old chapel in Town Road

Hanley into a restaurant gave new life to a building facing demolition.

In renovating Longton Cemetery Lodge I’m merely bringing the past into

the present. It’s exciting.”

Longton Cemetery -

Registrar's office

Diane’s new home was built in 1877, the year Longton cemetery opened.

“Its first occupant was a chap name Joseph Ashworth who was appointed

registrar and accountant by Longton Borough Council,” says historian Steve

Birks. “Joseph, a bachelor age 47 and his housekeeper sister Mary, age 49

and also single, came from Yorkshire, but little is known of their

previous lives.”

According to the council minutes Ashworth had an annual salary of £100

with the house added rent free. Gas and other services were also included

but exclusively for the office. Victorian prudence no doubt influenced the

Ashworth’s to spend most of their time in the office, a pleasant

sun-filled room by the front entrance.

“I love the office,” says Diane. “Even the original wardrobe safe is still

here. Nothing has been altered from those times and even now I expect to

be greeted by a wing-collared registrar wearing a morning coat and a black

top hat. It’s as though I’m living inside Victorian history.”

What about the neighbours, I ask.

“Oh I don’t anticipate trouble from them,” she laughs.

|

Longton cemetery off Spring Garden Road is typical Victorian parkland

laid-out in a rectangle of about 21 acres extended four times to

accommodate the increase in burials.

“The ground was originally owned by Mr J Edwards-Heathcote, a member of

the family that, along with the Duke of Sutherland, seemed to own most

of Longton. But he didn’t give his land away. Instead he charged Longton

Council £500 an acre thereby pocketing a cool ten grand. All this took

place when local boroughs were being compelled to provide new burial

space for its dead. Until 1650 most parishioners were buried in vaults

inside the church or in land surrounding them known as churchyards. But

when the churchyards became overfull, private cemeteries became a

popular option. Except for the poor whose population in the new town

centres was burgeoning rapidly,” says Steve.

The first public burials were tested in Norwich in 1819. But it was slow

to take hold as people feared detachment from church proximity. However,

by the middle of the 19th century urban churchyards were so

crowded and polluted that legislation was introduced to compel local

authorities to provide land for public burials. London’s Metropolitan

Interment Act of 1850 was the first, soon to be extended across the

country in 1853. |

“In 1860 Hanley became the Potteries’ first authority to comply with this

legislation,” says Steve, “Longton followed seventeen years later. This

was probably because of the unavailability of public land and the tricky

negotiations with other landowners before accepting Edwards-Heathcote’s

transaction of convenience. Anyway the land was divided up into partitions

of religious belief. Five acres was allotted as the Church of England

burial-ground. Beside this was the Nonconformists’ plot. And some other

part was set aside for the Roman Catholics. The superb listed central

chapel is a joy to look at and was designed locally and built by a Walsall

company with timber frames and Welsh slate roofs.”

Longton Cemetery -

Chapels

There are actually two chapels beneath one roof; Nonconformist and

Anglican. Each has three bays either side of an arched entrance beneath an

impressive tower designed with two stages of ornate timber panels and a

small spire. The main entrance has segmental archway gables with stained

glass quatrefoil windows and decorative timber panelling.

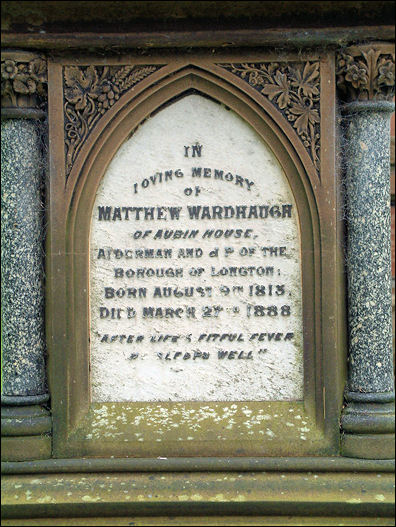

Grave memorial of

Matthew Wardhaugh

“The surrounding land is relatively flat,” Steve adds. “But possibly

because of its late construction many of Longton’s Victorian notables are

buried elsewhere. Nevertheless the grave of Matthew Wardhaugh is here. He

was a Victorian theatre proprietor who built the Royal Victoria Theatre in

Berry Bank, Stafford Street, now called The Strand. He wrote and performed

at least 50 plays. Most popular was his last play, My Little Wife

alternatively known as Nuts to Crack. Yes, it’s true!”

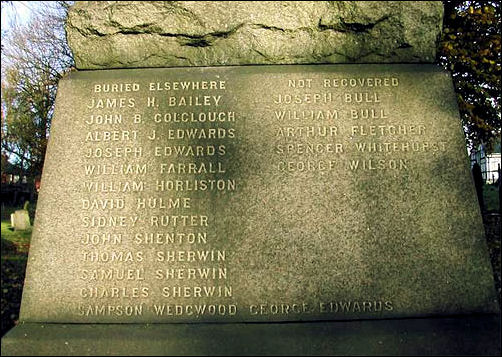

the names of those buried

in other burial grounds

and those not recovered

Another fine memorial is the granite tribute to the 64 miners killed in

the Mossfield Colliery explosion in 1889. The remains of 45 miners are

buried here together. Another 14 are buried elsewhere. But perhaps the

saddest are the five names listed beneath the simple stone-carved

valediction ‘not recovered’.

more on Longton

Cemetery

more on Longton

Cemetery

|

![]()

![]()

![]()