|

James Brindley

- 'bad planning or pioneer of transport engineering?'

click the

"contents" button to get back to the main index & map

next: the boatman's walk to Kidsgrove

previous: Adams & Greengates, Tunstall

|

Historian Fred Hughes

writes....

Canal pioneer James Brindley might have been a brilliant engineer

but did he hack it as a planner? There’s no doubt that his Grand Trunk

Canal streamlined transportation like nothing since the Roman Roads. But

why didn’t he put a towpath through Harecastle Tunnel. Surely he must have

seen that taking the horses over the hill while boats were legged through

would result in troublesome delay. Was it bad planning or something else?

|

“The completed project which opened in 1777 after eleven years tunnelling,

certainly wasn’t designed high or wide enough for horses,” agrees

historian Steve Birks. “Brindley chose the option of propelling the boats

through the tunnel between Tunstall and Kidsgrove by casual labourers

lying supine and pushing along the roof and the sides with their legs. It

was hard work and it took three hours.”

See what I mean – bad planning.

“Well in fairness to Brindley the overall journeys to the ports of

Liverpool and Hull were speeded up spectacularly, and the breakage of

carriage was virtually eliminated,” contends Steve. “But the popularity

of the canal highlighted Harecastle’s logjam situation as hundreds of

boats queued to get through. Fifty years later Thomas Telford was

commissioned to build a second tunnel taking a quarter of the time that

Brindley took, mainly due to the advancement of engineering technology.”

So why didn’t Brindley foresee the bottleneck problems, he was after all

undertaking a superlative communications innovation that some were calling

the 8th wonder of the world even before it opened. Andy Perkin

is chairman of Potteries Heritage Society and a canal enthusiast. |

Portrait of James Brindley from Samuel Smiles,

Brindley is armed with his surveying equipment.

“You need to understand who James Brindley was and what he was doing at

the time,” says Andy. “He was a trained millwright who developed

exceptional skills in dealing with the control of water. Brindley was

miles ahead of anyone else in mine drainage and flooding. Employed by the

Duke of Bridgwater as a consultant engineer to work with the Duke’s own

engineer John Gilbert, they built a canal from Worsley to Stretford in

1761.

This caught the eye of Josiah Wedgwood who wanted Gilbert to construct a

canal for transportation of clay to the Potteries and ware to the ports.

With Gilbert he’d get Brindley. But Gilbert wasn’t available so Brindley

came alone. Straightaway unique problems were seen negotiating Harecastle

Hill at the bottom tip of the Pennines.

He couldn’t climb over the hill because he couldn’t get water up there.

Going round the valley through Bathpool would have added five miles to the

journey and more construction time involving intense soil mechanics. You

have to remember that Brindley was a mine and water engineer, so he stuck

to what he knew best. And of course he had to meet the budget of his

commissioners.”

|

But why no towpath, I wonder.

“Again we shouldn’t forget that an undertaking of such magnitude had

never been done before. Brindley was dealing in exacting innovative

measurement and he planned his tunnel to meet nine-foot diameter

dimensions in order to determine a seven-foot width of the boat.

Why – because of financial restrictions. The Mersey canals and existing

manufactured waterways were fourteen-foot wide and there’s no doubt that

had the resources been available Brindley would have gone for

fourteen-feet. The compromise seven-foot width on his canal at least

allowed for two boats to float side-by-side at their destination. The

financial constraints were mainly governed by the cost of getting

through Harecastle.

A towpath was never an option. Retrospectively it was like building the

original M1 with dual carriageways; nobody envisaged there’d be so much

traffic a decade later.”

How did Telford’s tunnel improve things?

“Well the commissioners had been taking advantage of the coal found during

the excavations of Brindley’s tunnel and cut a number of branches inside

purely to get the minerals out,” Andy explains.

“This made navigation more difficult. Telford sealed off these mine

warrens inside Brindley’s tunnel while he was constructing his new tunnel

which he designed to a diameter of thirteen-foot including a purpose-built

towpath throughout its length. There’s no doubt Telford’s tunnel was

state-of-the-art. But of course fifty years had passed and the Industrial

Revolution had introduced startling engineering advances. Nevertheless, in

his time everybody was in awe of Brindley.

He was an engineering genius whose outstanding ability literally exploded

people’s minds.” |

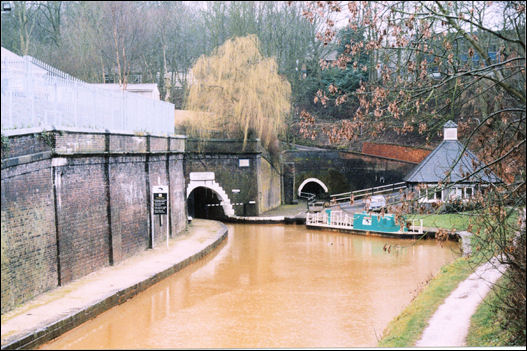

North entrance, the Telford tunnel to the left and Brindley's to the

right

These days the two tunnels sit side-by-side and the Telford Tunnel

is a very popular experience for pleasure boat tourists. David Fearn is

one of two British Waterways tunnel stewards on duty. He tells me that

since the increase of canal cruising some 6000 boats pass under Harecastle

each year.

“Regulations allow for a maximum convoy of eight boats each way,” says

59 year old David. “I’m based at the Kidsgrove end where I open the

tunnel gates in wireless conjunction with the gatekeeper at the other

end. It takes about forty-five minutes to pass through. Boats still

queue at each end, but people are patient.”

David and his wife Frances are retired. They live on the canal and travel

around entertaining with karaoke in pubs wherever they set anchor.

“Being a tunnel gatekeeper is a responsible job. But I tell you the only

trouble I get is keeping swans from swimming through,” David grins. “See

those two – Frances calls them Tip and Top – they’re here every day and

it’s a devil of a job to keep them out.”

Later I meet up with the Shaw family from Llandudno Junction. They’ve come

to Stoke on Trent especially to experience the journey through Telford’s

tunnel.

“It’s something we’ve wanted to do for ages,” declares parent Nigel Shaw.

Narrowboat leaving the south entrance of Tomas Telford's tunnel

And something I’ve always wanted to do is to follow the horse’s route over

the hill to meet my boat on the other side. The Shaw’s and I arrange to

put this to the test, they by water and me by road. I’ll tell you how we

went on next week.

next week: over Harecastle hill

click the

"contents" button to get back to the main index & map

next: the boatman's walk to Kidsgrove

previous: Adams & Greengates, Tunstall

|